|

|

|

|

| Adherence |

|

| Adherence: Introduction |

| What is adherence? |

| Why is adherence important? |

| Why is adherence so important now? |

| What influences how well people adhere? |

| How can adherence be improved? |

| References |

|

|

Adherence: Introduction

Adherence greatly influences the outcome of antiretroviral therapy, but achieving good adherence is a considerable challenge. Many people with HIV/AIDS find it difficult to follow their prescribed treatment regimens and problems can be encountered at any time.

People with HIV/AIDS, who adhere well to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), have an excellent opportunity to delay the onset of symptomatic illness for many years. If they are to achieve this goal, however, there are certain obstacles to overcome.

Good partnerships between patients and their healthcare providers can help to optimise adherence and overcome the challenges associated with taking HAART.

|

|

|

What is adherence?

Definition and forms of adherence

Adherence can be defined as 'the extent to which a therapeutic regimen is correctly taken'.1,2

In this definition, the word �correctly� is important � adherence involves taking:

- the correct drug(s)

- the correct quantity of drug(s)

- each drug at the correct times

- each drug with the correct diet.

Optimal adherence is achieved when all of the above criteria are observed � in practice most patients will not achieve 100% all of the time.

Negotiating and agreeing a course of action

The best possible clinical outcome is usually attained when the patient and prescriber negotiate a course of action.3 This is because optimal adherence is most likely to be achieved when the patient commits to an agreed therapeutic strategy.4 If the prescriber simply instructs the patient to follow a course of action without negotiating, both adherence and clinical outcome are likely to be suboptimal.

Top

|

|

|

Why is adherence important?

To maintain adequate drug concentrations

- Taking a drug at the right time each day ensures that adequate plasma and tissue concentrations of that drug (or its active metabolites) are achieved and maintained. In the case of HIV/AIDS, drug levels should always be high enough to inhibit HIV replication.

- Some drugs have a clearly defined therapeutic range: a range of plasma concentrations below which there is loss of effectiveness and above which there is an increased likelihood of side effects. Good adherence to a prescribed regimen helps ensure that plasma drug concentrations remain within the therapeutic range throughout the dosing interval. Low plasma drug concentrations may result from missing a dose, taking a dose too late, non-observance of administration requirements, or drug interactions. Conversely, high concentrations can occur as a consequence of inadvertent or deliberate overdosage, or from drug interactions.

- In the context of HIV/AIDS, non-adherence can permit plasma drug concentrations to fall to levels that are insufficient to inhibit viral replication.5

- Antiretroviral drugs can be eliminated from the body quite rapidly. This is why missing two or more consecutive doses � often referred to as a �drug holiday� � is usually highly undesirable.

To prevent virological failure

The main purpose of antiretroviral therapy is to inhibit viral replication and prevent damage to the immune system.

- If viral replication is inhibited and the immune system is able to eliminate virus particles from the body faster than they are being produced, the amount of virus in the plasma � the plasma viral load � decreases and damage to the immune system is restricted.

- If viral replication is completely (or almost completely) inhibited and the immune system is sufficiently healthy, virtually all of the existing virus is cleared from the body and the plasma viral load falls to below the limit of detection (<50 HIV RNA copies/mL).

- If viral replication is not successfully inhibited, however, the viral load can increase.

- When HIV is allowed to replicate freely and the viral load of a person taking antiretroviral therapy increases, virological failure occurs. Virological failure does not mean that the virus has failed, it means that the virus has in fact succeeded, in the sense that it (or at least some of it) is able to replicate. This is a highly undesirable situation.

- Virological failure can occur when the concentration of an antiretroviral drug falls below its therapeutic range. In this situation, the virus replicates faster than it can be cleared by the immune system.

-

The ultimate goals of HAART are maximal and sustainable suppression of plasma viral load to <50 copies/ml and/or to (partial) restore the immune function by increasing the CD4+ T cell counts.8 To achieve this goal, good adherence is essential.

To prevent drug resistance

- In addition to inhibiting viral replication and preventing damage to the immune system, antiretroviral therapy aims to limit the occurrence of drug-resistant virus.

- If HIV is allowed to replicate in the absence of antiretroviral therapy, drug-resistant forms of the virus will usually remain rare, but the plasma viral load will usually increase rapidly. In this situation, most of the existing HIV will persist in its most common form � often referred to as �wild-type� virus � the variant that initially infects most people.

- If HIV replication is completely (or almost completely) inhibited by adequate concentrations of effective antiretroviral therapy, drug-resistant forms of the virus will remain rare and the plasma viral load will stay low. This means that no new forms of HIV � including drug-resistant variants � can emerge because their very existence is dependent on the ability of the virus to replicate. If the virus cannot replicate, the viral population cannot adapt.

- If HIV is allowed to replicate in the presence of inadequate antiretroviral drug concentrations, however, the plasma viral load will increase and drug-resistant forms of the virus are liable to become more common. These forms will be more successful than others at replicating in the prevailing conditions. In time, most of the virus will become resistant to the antiretroviral drug(s) being used and the viral load will increase, unless prompt action is taken.

- When the viral population has become resistant to one or more components of a drug treatment regimen, it can become impossible to achieve plasma drug concentrations that are high enough to inhibit viral replication. In such cases, it is necessary to change to an alternative therapy.

- Some forms of HIV � often referred to as �cross-resistant� forms � are resistant to the highest clinically attainable concentrations of more than one antiretroviral drug. The existence of these cross-resistant variants can considerably restrict the available therapeutic options.

- The best way to minimise the impact of drug-resistant forms of HIV is to ensure good adherence to prevent them from emerging in the first place.

Top

|

|

|

Why is adherence so important now?

The treatment of HIV/AIDS has changed

Good adherence to antiretroviral therapy has always been a key issue. Since the introduction of HAART, however, it has become increasingly important. This is because:

- The advent of HAART means that more people with HIV/AIDS than ever before are being prescribed regimens containing multiple antiretroviral drugs.

- The effectiveness of HAART, compared with previously used antiretroviral therapeutic regimens, means that patients are taking medication for longer than ever before.

- Long-term experience of HIV/AIDS and taking antiretroviral therapy means that many patients feel they can monitor their own healthcare and do not need to visit their physician regularly.

- Some of the antiretroviral drugs (usually protease inhibitors or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors) have a narrower therapeutic range than some of the other antiretroviral drugs (usually nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors).

- A trend towards the increased use of regimens with lower recommended dosing frequencies (e.g. once daily administration) and/or regimens containing fewer pills, means that it is more important than ever to take the doses that are prescribed.

Poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy remains common

Despite the desirability of good adherence, non-adherence is a widespread phenomenon that occurs among all sections of society, including people with HIV/AIDS.7

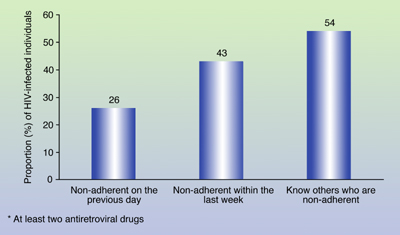

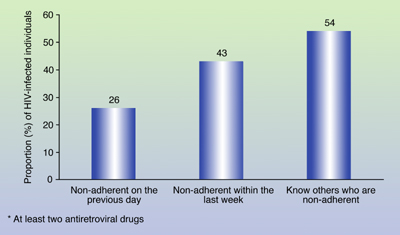

- In a national telephone survey, conducted in the USA and involving 655 people with HIV/AIDS, almost one-half admitted to having been non-adherent at some time during the past week and over one-quarter admitted to having been non-adherent on the previous day (Figure 1).8

Figure 1. Proportions of people with HIV/AIDS, currently being prescribed antiretroviral therapy,* who are non-adherent or know others who are non-adherent.

* At least two antiretroviral drugs

Source: Gallant JE, Block DS. Adherence to antiretroviral regimens in HIV-infected patients: results of a survey among physicians and patients. JIAPAC 1998; 4:32�35.

Top

|

|

|

What influences how well people adhere?

Everyone is different

It can be useful to classify people into groups in order to make sense of the differences between them. Sometimes the most obvious groupings prove to be useful, but on other occasions categorising people in this way proves to be unhelpful.

There is no consensus regarding which factors make an individual more or less likely to adhere to antiretroviral drug regimens.2,6 Commonly used groupings, such as socio-economic status, educational level, gender and ethnicity are, at best, poor predictors of adherence and, at worst, useless predictors of adherence.

The desire and ability to adhere to antiretroviral therapy seems to be dictated by subtle differences between people.2 These include differences in:

- available information or knowledge

- attitudes and beliefs

- skills and abilities.

The causes of non-adherence can best be identified, and possible solutions to it proposed, if the patient and physician have a good mutual understanding. It is therefore important for these people to form a good relationship based on mutual trust and respect.

Many inter-related factors

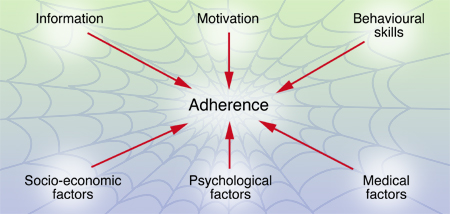

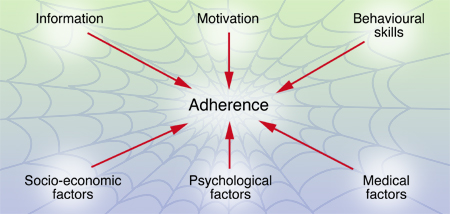

Numerous factors are associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy.9 Sometimes these factors are grouped into one of three categories: information, motivation and behavioural skills. On other occasions they are placed into three different categories: socio-economic factors, psychological factors and medical factors.

Adherence can be considered to lie at the centre of a complicated web of inter-related factors, each of which belongs to a certain category (Figure 2). Any one or more factors, in any one or more categories, might influence how well an individual adheres to antiretroviral therapy.

Figure 2. The web of factors influencing adherence

Factors that can affect adherence

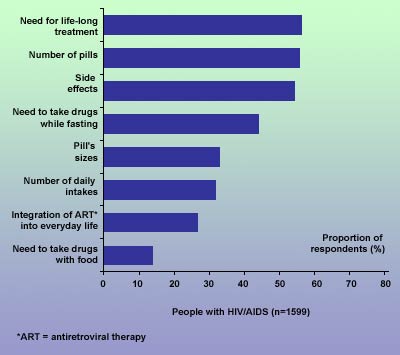

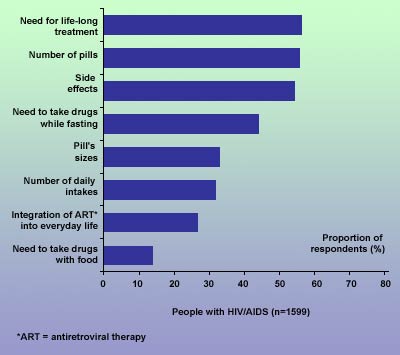

Although the factors that influence adherence vary from person to person, attempts have been made to identify those that are most common. Some have been identified in a French national survey, performed in 1999.10 In this study, the opinions of people with HIV/AIDS differed from those of physicians (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Perspectives on adherence difficulties among physicians and people with HIV/AIDS in France

* ART = antiretroviral therapy

Source: Raffi F. Presentation at the 2nd International HIV/AIDS Colloguium, Guadalajara, Mexico, 18�19 May 2000.

It is widely recognised that the following factors are often associated with an increased risk of poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy:11,12

- Large number of medications � the larger the number, the greater the likelihood of poor adherence

- Complicated therapeutic regimens � includes the number of times per day that pills must be taken, escalating/de-escalating schedules and special dietary restrictions

- Demanding storage requirements for medications � includes the need to keep medications refrigerated and dry

- Dosing requirements that interfere with the patient�s lifestyle � includes the need to alter the timing of meals and, if dosing must be concealed from others, additional activities of daily living

- Poor communication with physicians and other healthcare professionals

.

Top

|

|

|

|

How can adherence be improved?

The findings of a telephone survey, performed in the USA, provide some indication of what interventions are likely to improve adherence in a large proportion of people with HIV/AIDS.6 As part of this survey, 655 patients and 100 physicians with experience of treating at least 50 people with HIV/AIDS were asked: �What could be done to improve adherence to regimens to treat HIV-1 or AIDS?� The availability of an alarm pillbox was the answer most often given by the patients, while fewer doses per day or simpler dosing regimen was the answer most often given by the physicians (Table 1).

Table 1. Unaided responses to the question: �What could be done to improve adherence to regimens to treat HIV-1 or AIDS?�

|

Improvement |

Patients

(%)

n = 665 |

Physicians

(%)

n = 100 |

|

Alarm pill box |

15 |

0 |

|

Fewer doses per day or simpler dosing regimen |

10 |

29 |

|

Have medications without food restriction |

9 |

3 |

|

Fewer pills per dose or per day |

8 |

28 |

|

Once daily dosing |

5 |

28 |

|

Fewer adverse effects |

3 |

15 |

|

Other or no opinion |

50 |

17* |

|

* These included easier local availability of drugs, easier process for refilling of prescriptions on time, improving taste, availability of drug while on holiday and improving efficacy

Note: Some physicians and some patients listed more than one response

Source: Gallant JE, Block DS. Adherence to antiretroviral regimens in HIV-infected patients: results of a survey among physicians and patients. JIAPAC 1998; 4:32�35. |

An expert panel convened by the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation recently reached some measure of consensus regarding the interventions most likely to be associated with improved adherence.13 Some of these are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Some interventions associated with improved adherence

- Pharmacist-based adherence encounters/clinics

- Adherence encounters at each visit, often multi-disciplinary

- Reminders, alarms, pagers, timers on pillboxes

- Patient education aids, including regimen pictures, calendars, stickers

- Clinician education aids (e.g., medication guides, pictures, calendars)

Source: Panel on Clinical Practices for Treatment of HIV Infection convened by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. February 4th, 2002.

Available at: http://www.hopkins-aids.edu/guidelines/adult/gl_adult.pdf |

Lists of actions aimed at improving adherence have been produced by several different community-based organisations. For example, the AIDS Project Los Angeles (APLA) list14 includes many practical suggestions, any one or more of which may prove to be helpful to an individual who has been prescribed antiretroviral therapy. Table 3 lists some of these suggestions.

Table 3. Suggestions for improving adherence designed for people with HIV/AIDS

- Keep water by your bed so that you can take your pills in privacy

- Choose a regular time and place to count out all of your pills for the following week

- Buy a beeper or watch with an alarm

- Tape your dosing schedule to your refrigerator door

- Ask someone you live with to help you remember to take your pills at the correct time

- Ask your healthcare provider for detailed explanations

- Be honest with your healthcare provider about missed doses or doses taken incorrectly � otherwise they cannot help you improve your adherence

- Find out from your physician or pharmacist what to do if you miss a dose

- Plan ahead for changes to your usual routine, such as holidays

- Share your ideas for improving adherence with other people

Adapted from: Wongvipat N. 20 Tips for Sticking to Your Meds. Positive Living, December 1998.

Available at: http://www.thebody.com

|

Top

|

|

|

References

1. Tsasis P. Adherence to highly active antiviral therapy. AIDS Patient Care 2001; 15:109�115.

2. Andrews L, Friedland G. Progress in HIV therapeutics and the challenges of adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2000; 14:901�928.

3. Friedland GH, Williams A. Attaining higher goals in HIV treatment: the central importance of adherence. AIDS 1999; 13 (Suppl 1):S61�S72.

4. Klauss BD, Grodesky MJ. Assessing and enhancing compliance with antiretroviral therapy. Nurse Practitioner 1997; 22:211�219.

5. Wright MT. The old problem of adherence: research on treatment adherence and its relevance for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2000; 12:703�710.

6. Gallant JE, Block DS. Adherence to antiretroviral regimens in HIV-infected patients: results of a survey among physicians and patients. JIAPAC 1998; 4:32�35.

7. Tseng AL. Compliance issues in the treatment of HIV infection. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1998; 55:1817�1824.

8. Cinti SK. Adherence to antiretrovirals in HIV disease. AIDS Read 2000; 10:709�717.

9. Miller LG, Hays RD. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy: synthesis of the literature and clinical implications. AIDS Read 2000; 10:177�185.

10. Raffi F. Presentation at the 2nd International HIV/AIDS Colloguium, Guadalajara, Mexico, 18�19 May 2000.

Top

|

|

|

|

|

|