|

|

|

| Last updated on : 14-Oct-04 |

|

|

| HIV disease and management |

|

| Clinical features of HIV infection |

| Opportunistic infections and AIDS-related malignancy

|

| Clinical management of HIV infection

|

| What can HAART achieve? |

| HAART in practice |

| Primary HIV infection |

| Established HIV infection |

| Considerations for changing the HAART regimen |

| Antiretroviral agents |

|

|

Clinical features of HIV infection

Although little is typical about HIV infection at an individual level, the detailed clinical course of HIV infection being unique in each case, the natural history of the infection can be described in the following general terms.

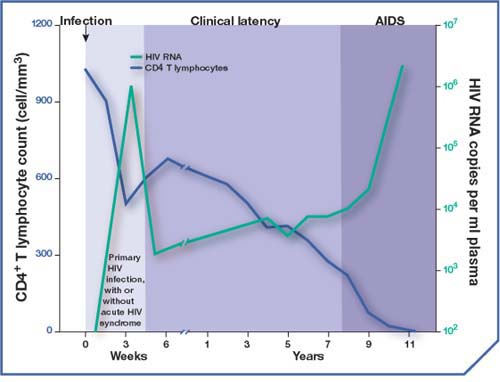

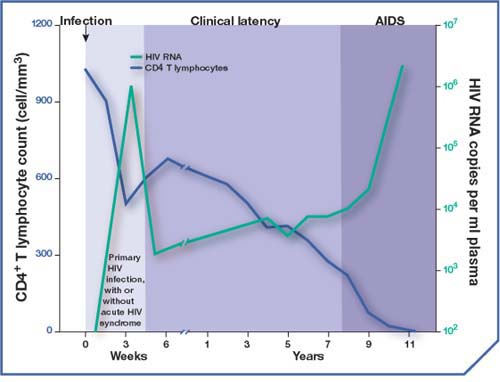

Typical course of HIV infection (modified from Fauci et al., Ann Intern Med 1996)

Primary HIV infection

Within a month or two of initial infection by HIV, some people may experience the acute HIV syndrome, with flu-like symptoms, and possibly a rash, lasting just a few weeks. In others, however, there may be nothing at all to indicate their infection with HIV.

Whether or not there are any symptoms, the first few months following primary HIV infection (PHI) are a time of extensive viral replication. Levels of virus circulating in the blood during this time will be high – a high viral load. Numbers of immune system CD4+ cells fall as they succumb to the first waves of viral infection. CD4+ count drops.

PHI triggers an immune response directed against HIV, and initially this is effective in clearing virus and infected cells from the blood. As a result, by the end of PHI viral load is reduced and the CD4+ count raised.

HIV disseminates widely in the body during PHI, however, and it reaches cells in the lymphatic system and other body compartments, like the brain, where it can sit out this immune response. These reservoirs of HIV are one reason why it is impossible to eradicate the virus entirely with current treatment.

Clinical latency

After PHI, many years may pass during which there are no clinical symptoms of HIV infection. This clinical latency makes it appear as though the virus might be inactive, but in fact HIV remains extremely active throughout the course of infection. Even during clinical latency HIV is replicating prodigiously. For a while, however, the immune system is able to contain the virus to some extent, and the viral load and CD4+ count change relatively slowly.

AIDS

For some time the body and the virus maintain a dynamic equilibrium of sorts.

Eventually, however, if HIV is allowed to replicate unchecked, this delicate equilibrium is broken, and the virus overwhelms the immune response and the body’s ability to replace CD4+ cells.

When this happens, viral load skyrockets as the virus once again becomes present in huge numbers in the blood. At the same time, the population of CD4+ cells is rapidly depleted.

By this stage HIV infection can inflict harm on the body directly, affecting many tissues, including the nervous system, gastrointestinal tract, muscles, red blood cells and kidneys. Alongside this, the weakened immune system means a person with AIDS is unable to defend themselves against opportunistic infections and malignancies, which are the principal causes of illness and death from HIV disease.

Top

|

|

|

Opportunistic infections and AIDS-related malignancy

People with advanced HIV infection are vulnerable to diseases that rarely threaten those with a healthy immune system.

These diseases are among the most prominent causes of illness and mortality in HIV-positive people, and their occurrence is often used to define the transition to AIDS.

Opportunistic infections

Microorganisms that do not ordinarily cause disease can become pathogenic in someone with an impaired immune system – they take the opportunity of a weak immune response to establish infection.

People living with HIV can become susceptible to a wide range of these microorganisms, and so-called opportunistic infections are the hallmark of the immunodeficiency caused by HIV.

AIDS-related malignancies

By damaging the immune system, HIV infection leads to a significantly increased risk of certain types of cancer. Exactly why immunosuppression should be such a risk factor for these particular cancers is not clear, although it is possible that they are triggered by an infectious agent.

One of the most common of these AIDS-defining cancers is Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), a cancer of the blood vessels, which is characterised by purplish lesions on the skin. People with HIV infection /AIDS are many thousands of times more likely to develop KS than healthy people.

Another cancer that is common in people with HIV infection/AIDS is non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph nodes that can progress to involve the gastrointestinal tract, the nervous system, bone marrow, lungs and skin.

|

|

|

These are some of the most common opportunistic infections

An infection caused by the fungus, Candida albicans, and affecting the mouth, throat or vagina. Candida is the most common HIV-related fungal infection, and can occur even in those with a fairly high CD4+ count, although it is more likely if the count is less than 200/mm3.

CMV is a herpes-type virus that can cause eye disease and blindness.

In developed countries, around 50% of all adults – not just those with HIV infection – are infected with CMV, but it is rare for the virus to cause disease unless the CD4+ count is lower than 100/mm3

CMV usually affects the eyes (retina), colon, and throat, although it can infect almost any other internal organ.

- Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

HSV can cause oral herpes (cold sores) or genital herpes. These are relatively common infections in the general population, but they can be much more frequent and severe in someone infected with HIV. They can occur at any CD4+ count.

- Mycobacterium avium

complex (MAC or MAI)

Bacterial infection with Mycobacterium avium or M. intracellulare can cause recurring fevers, painful intestines, weight loss, and anaemia

Almost half of those with late-stage HIV disease (AIDS) are infected with the MAC bacteria, although not everyone will have symptoms. The risk of MAC is higher for people with a CD4+ cell count below 50/mm3.

- Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP)

PCP is the most common, life-threatening opportunistic infection. The risk of infection is greatest in those with a CD4+ count less than 200/mm3.

PCP virtually always affects the lungs, but other organs can be involved, including the lymph nodes, spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Symptoms include fever, a dry cough, chest tightness, and difficulty breathing.

|

|

|

Toxoplasmosis is a brain infection caused by the parasite, Toxoplasma gondii. It is one of the most common neurological infections in the world.

T. gondii can be contracted by eating raw or undercooked meat, or by contact with cat droppings. The risk of toxoplasmosis is greatest in those with a CD4+ count less than 50/mm3.

Tuberculosis is transmitted in aerosol form when a person with active disease sneezes or coughs. Once infected by TB, most people develop only latent infection and remain healthy. However, they do have the potential to become sick and infectious with active TB.

In someone with HIV infection, active TB often occurs early, and is sometimes the first sign that the person has HIV. As well as affecting the lungs, TB in someone with HIV can also affect non-respiratory tissue, such as the lymphatic system. Symptoms include cough, fever, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue. TB is more frequent in those with a CD4+ count less than 200/mm3 but can occur at any CD4+ count.

Top

|

|

|

Clinical management of HIV infection

Since it became available in the mid-1990s, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly reduced the morbidity and mortality of HIV infection, and transformed the outlook for people living with the disease. It has revolutionised the management of HIV infection, turning it from being centred largely on the control of opportunistic infections and the provision of palliative care into a long-term strategy for controlling a chronic condition.

Along with this considerable success, HAART has brought new challenges. The drug regimens are medically complex and can be difficult for patients to adhere to. The need to limit and manage adverse effects during long-term therapy, and to minimise the development of drug resistance and make the best use of available drugs, requires careful planning and constant attention.

Research into new antiretrovirals for the future is also important, and drugs with novel mechanisms of action are already being developed.

Top

|

|

|

What can HAART achieve?

So far, no way has been found to eradicate the virus from a person infected with HIV. Instead, HAART aims to suppress the replication of the virus as completely as possible and for as long as possible, in order to slow the progression of disease and potentially allow lost immune function to be restored.

The degree of viral replication is reflected in the level of HIV RNA present in the plasma – the viral load. The goal of HAART is to maintain viral load below detectable levels (currently 50 copies/mL) through effective and sustained suppression of viral replication.

Achieving this goal is no easy matter. Treatment complexity, adherence difficulties, drug resistance, side effects and long-term complications, and the need to sequence antiretroviral regimens effectively over long periods of time, all make the management of HIV a challenge for everyone involved.

Top

|

|

|

HAART in practice

Every decision regarding HAART is made on an individual basis, and is a matter for the person living with HIV and the healthcare professionals caring for them. In all cases, achieving the right balance of risks and benefits requires careful consideration of a wide and complex range of factors.

Some general principles do exist, however, and these are the basis for treatment guidelines like those published by the DHHS and the IAS.

Indications for starting antiretroviral therapy

Beginning antiretroviral therapy is the start of a potentially long and complex course of clinical management. Particularly careful consideration must be given to the initial choice of antiretroviral agents, because the first HAART regimen represents the best chance to achieve effective and sustained viral suppression.

Whenever the decision is taken to begin HAART, it is important that the regimen chosen is effective, well tolerated and capable of preserving future treatment options.

The DHHS guidelines currently recommend that HAART be offered in the following circumstances:

Primary HIV infection

- All patients with the acute HIV syndrome

- Those within 6 months of seroconversion

Established HIV infection

- Patients with symptoms ascribed to HIV

- Asymptomatic patients who have:

- a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3

or

- plasma HIV RNA levels exceeding 55,000 copies/ml (bDNA assay or RT-PCR assay).

Top

|

|

|

Primary HIV infection

Between 40% and 90% of people acutely infected with HIV are thought to experience the symptoms of the acute retroviral syndrome. Therefore, they can potentially be identified as candidates for early therapy. In addition, those who can pinpoint their initial infection within 6 months prior to seroconversion may also be considered.

Although clinical data are limited, the theoretical rationale for treating primary HIV infection is that it may:

- suppress the initial explosion of viral replication and limit the spread of the virus throughout the body

- preserve immune function

- potentially lower the viral load ‘set point’

- reduce the rate of viral mutation by suppressing replication

- reduce the risk of viral transmission

- decrease the severity of acute disease symptoms.

These potential benefits must be weighed against the risks associated with beginning HAART. For a person without symptoms, the decision whether to begin treatment which potentially could have adverse effects is a difficult one to make.

Top

|

|

|

Established HIV infection

The DHHS guidelines currently recommend antiretroviral therapy for all patients with established HIV infection who show any symptoms attributable to HIV, regardless of viral load.

This includes patients with advanced HIV disease/AIDS as well as those without AIDS but with symptomatic HIV infection, such as those with thrush or unexplained fever.

In patients with established HIV infection but without symptoms, the decision whether to begin HAART takes account of the viral load or the CD4 count, because in the absence of symptoms, the risk/benefit profile of HAART is different.

Benefit/risk profile of antiretroviral therapy in the asymptomatic HIV-infected person

Benefits and risks of early antiretroviral therapy

Benefits

- Potentially easier control of viral replication.

- Delay or prevent immunologic compromise.

- Lower risk of resistance if complete viral suppression.

- Potentially decreased risk of HIV transmission.

Risks

- Drug-related reduction in quality of life.

- Increased cumulative drug-related adverse events.

- Earlier development of drug resistance if viral suppression is suboptimal.

Benefits and risks of delayed antiretroviral therapy

Benefits

- Avoid negative effects on quality of life.

- Avoid drug-related adverse events.

- Delay the emergence of drug resistance.

- Preserve maximum number of treatment options for the future.

Risks

- Potential risk of irreversible damage to immune system.

- Possible increase in the difficulty of suppressing viral replication.

- Possible increased risk of HIV transmission.

Top

|

|

|

Considerations for changing the HAART regimen

Once someone has begun HAART, their response to treatment must be monitored to determine whether HIV is being suppressed effectively.

This is evaluated largely by measuring the viral load. Viral load is expected to show a 1 log10 decrease at 8 weeks, with no detectable virus within 4–6 months of beginning HAART.

Other parameters that can be measured include:

- adherence – excellent adherence is a critical success factor in HAART, and is routinely assessed

- CD4+ cell count – a persistent decline in CD4+ count may indicate therapy failure

- therapeutic drug levels – between individual patients there can be wide variation in the plasma concentration profiles of protease inhibitors (therapeutic drug monitoring may help to ensure plasma levels are optimal)

- drug resistance – it is possible to test HIV for resistance to antiretrovirals, and this can improve treatment by identifying drugs in the regimen which may be ineffective.

Specific criteria that indicate that a change of regimen may be necessary include:

- a reduction in plasma HIV RNA of less than 0.5–0.75 log10 by 4 weeks following initiation of therapy, or less than 1 log10 by 8 weeks

- failure to suppress plasma HIV RNA to undetectable levels within 4–6 months of initiating therapy

- repeated detection of HIV RNA after suppression to undetectable levels – viral rebound, which suggests the development of drug resistance

- a persistently declining CD4 count

Top

|

|

|

Antiretroviral agents

The antiretroviral agents currently available fall into three broad categories:

(1) Inhibitors of HIV reverse transcriptase –

reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTIs).

RTIs are further classified according to their structure as:

- nucleoside analogue RTIs (NRTIs or Nukes)

or

- non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs or Non-nukes).

(2) Inhibitors of HIV protease –

protease inhibitors (PIs)

Reverse transcriptase and protease are both enzymes that HIV produces to control essential steps in its life cycle.

- Reverse transcriptase – converts HIV RNA into proviral DNA

- Protease – cleaves the polyproteins into smaller proteins, thereby allowing the new viral particles to mature

(3) Inhibitors of HIV fusion –

fusion inhibitors (FIs)

Sometimes this class is also known as entry inhibitors (EIs). When HIV infects a cell, it goes through three main steps: binding, co-receptor attachment and fusion. Fusion inhibitors block the last stage in this process and prevent the virus from passing through the membrane and infecting the cell. Fusion inhibitors are, therefore, different to other classes in that they work outside of the cell rather than inside.

Combination therapies that inhibit different stages of the HIV life cycle make it much more difficult for the virus to replicate.

|

|

|

Licensed agents in the treatment of HIV infection are listed below. The generic name is shown first, followed by the acronym (in brackets), followed by the Trade name.

Reverse transcriptase inhibitors

NRTIs

- abacavir (ABC), Ziagen

- didanosine (ddI), Videx

- lamivudine (3TC), Epivir

- stavudine (d4T), Zerit

- zalcitabine (ddC), HIVID

- zidovudine (AZT, ZDV), Retrovir

- lamivudine/zidovudine (3TC/AZT), Combivir

- lamivudine/zidovudine/abacavir (3TC/AZT/ABC), Trizivir

- emtricitabine (FTC), Emtriva

- tenofovir (TDF), Viread

NNRTIs

- efavirenz (EFV), Sustiva

- delavirdine (DLV), Rescriptor

- nevirapine (NVP), Viramune

Protease inhibitors

- amprenavir (APV), Agenerase

- fosamprenavir (FPV), Telzir

- indinavir (IDV), Crixivan

- nelfinavir (NFV), Viracept

- ritonavir (RTV), Norvir

- saquinavir (SQV), Invirase/Fortovase

- lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r), Kaletra (this is a boosted PI that contains ritonavir)

- atazanavir (ATZ), Reyataz

Fusion inhibitors

- enfuvirtide (ENF), Fuzeon

Top

|

|

|

|

|

|